Support the roll-out of zero-emissions vehicles cross all modes

Net Zero Investment Plan

Area 7: Invest in new, decarbonised fleets (5.7%)

Accelerating the transition to sustainable transport involves electrifying corporate and leasing car fleets, van and truck fleets, and acquiring zero-emission trains, with targeted funding and incentives playing a crucial role in promoting widespread adoption and achieving ambitious climate goals.

Investment Areas

Fleet renewal Priorities

Electrification of Corporate and Leasing Car Fleets

Electrification of Van and Truck Fleets

Acquisition of Zero-Emission Trains

- Electrification of Corporate and Leasing Car Fleets

Electrification of corporate and leasing car fleets presents a significant opportunity for accelerating the transition to sustainable transport. A European ‘Marshall Plan’, akin to the post-COVID recovery plan, could play a pivotal role in expediting fleet renewal over a ten-year period. By providing targeted funding and incentives, Europe can encourage the widespread adoption of electric vehicles within corporate and leasing fleets, thus reducing emissions, promoting innovation and stimulating economic growth.

- Electrification of Van and Truck Fleets

Electrification of van and truck fleets is essential for achieving ambitious climate goals and reducing emissions from the transport sector. Investing in electrification of commercial fleets can yield substantial environmental and economic benefits.

- Acquisition of Zero-Emission Trains

As Europe transitions to zero-emission transport, there is a pressing need to acquire new zero-emission rolling stock to replace ageing diesel fleets. Given that the average lifespan of rolling stock in Europe is approximately 30 years, targeted investments in zero-emission trains will be crucial for phasing out diesel propulsion and advancing rail electrification efforts. Infrastructure managers and operators – particularly in Central and Eastern Europe where rolling stock fleets are older – stand to benefit significantly from investments in new zero-emission rolling stock. By supporting the acquisition of zero-emission trains, Europe can modernise its rail infrastructure, reduce emissions and promote sustainable mobility throughout the continent.

Eight steps for an efficient legislation to increase the share of zero-emission vehicles in corporate fleets

Greening corporate fleets initiative

Eight steps for an efficient European legislation in 2023

In June 2022, the European Parliament voted for a de facto ban on sales of internal combustion engines (ICE) vehicles by 2035. To reach this objective, the Parliament also voted in favour of creating additional measures, notably to support the demand for zero-emission passenger cars and light-commercial vehicles (ZEV) within the Union market (AM. 80). It is essential that these accompanying measures are as ambitious as those of the end goal. A fleet mandate to cover the period prior to 2030 would ensure that demand meet supply.

In May 2021, the Platform for electromobility, an alliance of 40+ industries, NGOs and associations covering the whole value chain and promoting the acceleration of the shift to electric mobility, outlined the benefits and opportunities of dedicated legislation to complete the decarbonisation of corporate fleets. This paper now provides policy makers with overarching principles that should lead the elaboration of the upcoming legislative proposal that will bind the electrification of corporate fleets.

1. Standalone legislation on private fleet

As indicated by the use of the plural ‘proposals’ in the approved text, we recommend that the European Commission prepare two separate, dedicated pieces of legislation; one on the private fleet, the other on the public fleet. While the latter should be addressed in the revision of the Clean Vehicle Directive (CVD), and invite Member States (MSs) to lead by example with ambitious electrification plan for public authorities’ fleet, we must note that 99%1 of fleet-owned cars are the property of private individuals. The dynamics between private and public fleets are also different in areas such as size, procurement rules, and thus should be treated separately. In addition, as the first reference period under the CVD has only just begun, we believe any revision to the Directive would be premature.

The priority should therefore be given to address the decarbonisation of private fleets, which represent more than 60% of EU sales.

2. Need for a Regulation

While the revision of the CVD is appropriate to decarbonise the public fleet, we believe a Regulation, rather than a Directive, is essential to electrify the private fleet. A Regulation would:

- Stimulate deployment of electric mobility throughout the EU before ICE phaseout, by accelerating decarbonisation of the corporate cars that drive more than 2.25 times further than individually owned cars.

- Boost zero-emission uptake in the B2B segment, for which the total cost of ownership is superior, because of higher annual mileages.

- Create a plentiful second-hand market that ensures affordability of zero-emission vehicles before 2035.

- Avoid the delays in implementation that a Directive might entail, such as those that can currently be seen with the Clean Vehicle Directive. While climate change remains an ongoing threat, the time needed to conclude negotiations on a Regulation would be compensated for by the inevitability of its direct implementation. A Regulation will reduce the transition time to electric mobility between those Member States that have already announced the phaseout of ICEs by 2030 and those yet to do so.

- Bring certainty to both EV manufacturers and those companies purchasing targeted fleets. Such certainty for manufacturers, along with ambitious CO2 emission performance standards for new cars and vans, will ensure that the supply of EVs is able to meet the EU’s climate ambitions. It will also help avoid companies competing for a limited supply of ZEVs.

- Introduce stronger safeguards than a Directive against potential Member State market distortions, notably in the form of unfair price increases for the private fleet owners.

3. Almost-complete decarbonisation by 2030

The final target should be 95% of new fleet purchases of passenger cars to be ZEVs by 2030. The last 5% would be difficult to decarbonise, both technically and economically, due to the existence of some specialty vehicles. Setting the final target at a lower level, or after 2030, would not unlock the 10 benefits of mandating the decarbonisation of corporate fleets.

In the area of light-duty vehicles, the market of vans is more limited in supply compared to passenger cars. Therefore, the sector should have both a dedicated trajectory and a dedicated fleet size threshold, above which the Regulation will apply. Vans, with their own specificities, cannot follow at the same pace as cars. Their lifecycle is longer (28 years average) and their usages are usually unique and adapted to specific professional needs. In order to respect the nature of this market, targets must be adapted accordingly. Platform members agree on the need to build a dedicated trajectory and targets for Light Commercial Vehicles (LCVs), although an impact assessment is needed to shape the timeline and the curve appropriately.

While a 95% final target for passenger cars would already ensure a certain level of flexibility, the text voted by the Parliament invites the Commission to also take into account regional disparities.

4. Flexibility measures

Targets should therefore be set at EU level rather than differing targets per Member State. This would prevent some arbitrage strategies from manufacturers and overpricing in those countries in which targets would have been higher.

Setting targets at a European level, based on a certain fleet size, would also ensure that large companies meet the fleet target in each Member State in which they operate. This would ensure that separate strategies are not in place in different countries. Currently, in the numerous electrification strategies of companies operating across Europe, efforts are being centralised on more advanced markets, setting aside those markets where electrification of transport is lagging behind. This must change, as a ZEV second-hand market should be developed in CEE Member States as a matter of urgency.

Given the need to decarbonise the B2B segment in every Member State, while simultaneously taking into account the current differing starting points and ability for companies to effectively procure new

ZEVs, we strongly suggest two types of flexibilities that could be granted. One, a delay of a maximum of two years of the mandate, and two, an increase in the minimum fleet size to which the mandate applies.

It is important that, when it comes to eligibility for such flexibilities, the two types should be applied either at Member State level or at company level. Whichever option is chosen, the flexibility requests should be reviewed and assessed by the European Commission to ensure harmonisation at EU level.

Flexibility is essential to ensure the fair transition to clean fleets, as are interim targets:

5. Interim targets

Interim targets are essential to ensure a gradual and smooth transformation of the European private fleets. Without ambitious short-term targets, and even taking into account the proposed flexibilities above, fleets covered by the Regulation would need to undergo drastic change shortly before the final deadline. An unanticipated increase in demand risks triggering uncertainties not only for the business models of fleet owners and users but also for the availability, sustainability and security of the value chain for ZEVs. Hence the importance of ambitious interim targets, clearly set ahead, to increase visibility for car manufacturers and fleet managers alike. The objective of the Regulation is to accompany the shift introduced by the de facto ban on sales of ICE vehicles for users, but also to ensure demand matches supply all along the transition.

Although setting an interim target for 2025 may seem a tight timeline for a legislation to enter into force in 2024, a 2025 target close to half of all newly procured vehicle in corporate fleets to be zero-emissions is reachable: market analysis show an organic share of ZEV in fleet purchases of up to 35%. A recent study, based on 1300 fleets representing over 46,000 vehicles across Europe, shows that nearly 60% of fleets could save money by transitioning to electric vehicles without any incentives.2 With little impact – and a positive one in most cases – on the purchase decisions of corporate fleets, such a target for 2025 would allow the creation of a secondary market to make EVs more accessible by 2030. A linear trajectory for a convenient transition to 95% final target procurement would then set the following interim targets:

(1) by 2025, 45% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission;

(2) by 2026, 55% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission;

(3) by 2027, 65% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission;

(4) by 2028, 75% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission;

(5) by 2029, 85% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission;

(6) by 2030, 95% of renewed vehicles are zero-emission.

6. Stock target

In addition to renewal targets focusing on the share of ZEV in the new acquisitions of corporate fleets, stock targets should also be included. Stock targets would avoid creating long-term leasing contracts on ICE vehicles just before each interim renewal targets enter into force. On top of annual targets for new vehicles entering the fleet, a 75% zero-emission target for the whole fleet by 2030 should be inserted to prevent companies signing long-term ICE lease or bulk-buying ICE vehicles in 2023 or 2024, in other words before the regulation enters into force.

7. Reporting

Reporting should be managed by Member States and supervised by the European Commission. Alternatively, France offers a testbed for reporting obligation for a similar mandate. In France, there are reporting obligations for all companies based in the country that fall under the decarbonisation mandate of January 2021. Declarations are made on an annual basis, and are reported on the French government’s open data website. These include a CSV file with information relating to company registrations, descriptions of the fleet and of the low emissions / very low emissions renewal of vehicles Y1. Member States could rely on such a declarative open data by the companies to then aggregate the input and send it to the European Commission for compilation. A control, based on licence plates registered to a national registration agency or equivalent, should be conducted by the Government to verify the data entered by companies for their annual reporting.

Member States should, on an annual basis, send the aggregated data collected nationally to the European Commission to provide an EU-wide overview of the situation.

8. Revision of the objectives

The Regulation should introduce a review clause, by 2028, in the event that the objectives are not achieved. This clause would allow the European Commission to propose additional measures to ensure the Regulation is properly applied in every Member State.

Platform members also recognise the positive impact that such a mechanism would have on the decarbonation of heavy-duty vehicles. At the same time, platform members equally stress the importance of support mechanisms for the rollout office-based charging, from subsidies to tax discounts.

Mandating zero-emission vehicles in corporate and urban fleets: guidelines for reflection for policy makers

In a previous communication,

the Platform for electromobility,

an alliance of 45 industries, NGOs and associations covering the whole value chain and promoting the acceleration of the shift to electric mobility, called for a new single regulation dedicated to the complete decarbonisation of corporate fleets. Such fleets represent 63% of new registrations and, on average, drive more than double the number of kilometres of private cars. The largest leverage for CO2 reduction with reduced political risks. The Platform recommended adopting a gradual approach to eventually reaching the objective of 100% of new vehicle purchase in corporate fleets being fully electrified by 2030.

This paper follows up on the previous communication paper with the aim of providing policy makers with the information and figures to support the drafting of such new legislation. The elements presented below are intended to aid reflection on enshrining in law and implementing the EU Smart and Sustainable Mobility Strategy’s “actions to boost the uptake of zero-emission vehicles in corporate and urban fleets”. This commitment can be made concrete through a new EU legislative framework that mandates the transition to ZEVs (Zero Emission Vehicles) for company cars.[1]

A consensus on a regulation

Although the variables of such new legislation are being debated within industries and sectors, it is certain that a Regulation, rather than a Directive, is essential for a range of reasons. A Regulation will:

- Stimulate deployment of electric mobility in those countries where uptake is currently slowest. The logic for better-harmonised measures at the EU level arises from the need for the same level of effort against climate change within all Member States.

- Avoid the delays in implementation that a Directive might entail – such as can currently be seen with the Clean Vehicle Directive. With the climate change clock continuing to tick, the time needed to conclude negotiations on a Regulation would be compensated for by the inevitability of its direct implementation. A Regulation will reduce the transition time to electric mobility between those Member States that have already announced the phase-out of ICEs by 2030 (such as Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, and Ireland) and others.

- Bring certainty to both EV manufacturers and those companies purchasing targeted fleets. Such certainty for manufacturers, along with ambitious CO2 emission performance standards for new cars and vans, will ensure that the supply of EVs meets the EU climate ambitions and avoid companies competing for a limited supply of ZEVs.

- Introduce stronger safeguards than a Directive against potential Member State market distortions, notably in the form of unfair price increases for the private fleet owners.

Variables to consider within the Regulation and potential options

That said, a range of options for the Regulation mandating ZEVs for company cars can be considered. These include regulation application threshold, timeline, average fleet consumption or a mandate on new purchases, etc. Below, the Platform provides examples from the debate within certain Member States.

Application threshold:

There must be a balance struck between covering a large proportion of company cars in Europe while not overly impacting smaller companies, where such a mandate could become an excessive financial and administrative burden.

The Platform proposes to target the largest companies first, as it is possible to mandate the electrification of most company cars. Table 1 shows the share of company cars in Spain managed by companies, according to the size of their fleet. For example, by mandating companies managing 20+ vehicles (i.e. medium and large companies, representing only 6.8% of the total), it would be possible to electrify 55.2% of all company cars. France has already chosen such an approach (this example is detailed in Annex I of this paper).

As well as making the greatest impact with the lowest burden on the economy overall, targeting the largest fleets first would also make the implementation and enforcement of the legislation more efficient. It is easier to control and scrutinise large entities with dedicated fleet management services than it is for microenterprises. Establishing a distinction between private and business use of corporate vehicles for these smaller companies would entail onerous and disproportionate costs and an excessive administrative burden in keeping appropriate records.

Application timeline:

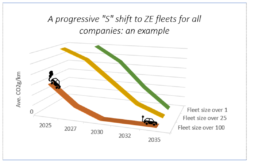

This approach would allow the adoption rate to follow an ‘S-shape’ curve, with a slow increase to 2025 due to difference in the cost acquisition of ZEVs. After 2025, and with price parity between ICE vehicles and ZEVs, the adoption rate will begin to accelerate. An EU target will provide a clear threshold for companies, while leaving flexibility for those Member States that seek to move faster towards their goal. Ideally, the mandate would apply to the fleets of the largest companies before applying to smaller fleets, given that – as time goes on – the acquisition cost of EVs will diminish and more charging infrastructure will become available.

In order to avoid social backlash, the objectives of emission reduction for 2030 were set at a moderate level. Acting more rapidly on company cars during the period 2025-30 with more ambitious levels would allow a significant impact on decarbonisation while avoid impacting those with the lowest incomes. Small- and medium-sized enterprises should be supported during the transition, as they lack the analytics and training resources of bigger companies.

Transition pace:

The steepness of the transition curve is also an element that needs to be considered. To make all newly procured corporate vehicles zero-emission by 2030 will require rapid uptake. To achieve this, there are different potential pathways (linear growth, exponential growth, ‘S-shaped’ curve, etc.), for which the efficiency, fairness and preparedness should be assessed in the impact assessment.

Enforcement, incentives and penalties:

In order to enforce the legislation, a first step would be to establish a clear reporting system to keep track of new procurement. As a next step, some type of incentive and/or penalties framework should be created. Belgium is an example of an early adopter of such fiscal incentives. The fiscal benefits for ICE company cars will progressively decrease in the country, ultimately disappearing by 2026. Meanwhile, the fiscal benefits for EVs will be maintained. In France, there is a bonus and a premium for conversion that will apply from 2022 with potential renewal.

The levels set for such variables should be discussed with industry and stakeholders throughout the legislative process and consultation phases. This political objective will be translated with specific measures in each Member State. A recent study by T&E has shown how a wide range of measures, mostly fiscal, can be activated at national level. The study showed that, once applied, such measures are effective. If Member States decide not to enforce incentivising measures for companies, then penalties may fall on those companies that fail to comply.

[1] In the document, “company cars” are defined as any passenger cars that are part of a larger fleet within the commercial market channel. There are three common categories; i) short-term rental / rent-a-car; all registrations made by rental car companies; ii) OEMs / dealers / manufacturers – demonstrators, loan cars, one-day registration, 0km, registrations made by manufacturers against themselves; iii) true fleets – all except the above categories.

Platform’s proposals to boost zero-emission vehicles in corporate and urban fleets

Platform’s proposals to boost zero-emission vehicles in corporate and urban fleets

With the European Union agreement on -55% greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 2030, all economic sectors will have to pull their weight towards this goal. Unfortunately, the transport sector has a poor decarbonization track-record with emissions steadily growing since 1990.

Looking at all transport modes, road transport is still the largest emitter (71%) and will remain so in the near future[1]. Recently adopted CO2 emission performance standards, investment in charging infrastructure, etc. will eventually drive down emissions, but new initiatives aimed at “quick wins” are needed to fast-track decarbonization.

These initiatives should be based on the idea that when fighting against climate change and local pollution, not all vehicles are equal. Fleet vehicles (i.e. corporate fleets) drive on average 2.25 times[2] more than private cars. Public fleets, such as urban buses which account for 8%[3] (per passenger per km) of greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted by the transport sector, are also big players. Last but not least, as fleet vehicles are often parked in depots and large parking lots, their batteries could be used to optimise the RES integration and the use of smart charging could provide benefits to local utilities and to the whole power system[4].

Against that background, the Platform for electromobility welcomes the European Commission’s ambition to electrify public and corporate fleets recently introduced in the Smart and Sustainable Mobility Strategy.

In this paper, we share our insight and expertise to make this a reality. We first recommend ensuring an ambitious implementation of the Clean Vehicle Directive (CVD) for public fleets in all Member States (MS). Second, new legislation dedicated to the electrification of corporate fleets should be envisaged.

Implementing the Clean Vehicle Directive

While at its adoption in 2019, we expressed our enthusiasm that the CVD would pave the way for a broad deployment of clean vehicles across Europe – electric buses in particular – it seems likely that few MS will transpose the directive in time.

As of April 2021, only France has implemented the directive, and only a few more MS have started the transposition process which is due to be completed by 2nd August 2021. There is a risk that an unequal transposition of the directive will lead to fragmentated and non-harmonized access to clean transportation and its benefits for citizens between MS.

Recent bus registration figures also show that while the sales of electric buses are progressing, most countries are still nowhere near the CVD targets [6]. Therefore, we call the legislators to push for a better and faster implementation of the CVD in most MS. National governments should make the best use of available funds, including national and European recovery plans, to achieve the targets of the directive.

Electrification of public fleets covered by the CVD is only one step on the road to a 90% cut in transport emissions by 2050. Electrifying corporate fleets[7] constitute another powerful leverage towards the decarbonation of transportation in Europe.

Leveraging corporate fleets to curb emissions

Corporate cars represent millions of high-mileage vehicles circulating in Europe with a high turnover. They now also represent the main part of the car market in Western Europe. According to a recent Deloitte[8] report, in 2010 the private and corporate market segments were almost equally large in Western Europe (respectively 7.3 million vs. 7.2 million car registrations). In 2016, the balance had already tilted in favour of corporate cars (58%), and by 2021, Deloitte forecasts a share of new car registrations of 37% for the private and 63% for the corporate channel. In countries not covered by the study like Poland, corporate cars share in a new passenger car market is even larger, reaching 75% in 2020[9].

Corporate cars quickly become private cars via the second-hand market after an average ownership of 36 to 48 months. Most Europeans indeed purchase private cars after they used corporate functions[10]. The electrification of corporate fleets is therefore key to also electrify the whole stock (owned by individuals) with a reasonable time gap.

Corporate fleets represent 20% of the total vehicle park in Europe, 40% of total driven kilometers but is responsible for half of total emissions from road transport. Starting with corporate fleets is the quickest way to reach emission cuts.[11]

Additionally, corporate cars are highly visible in our cities. By leading by example and supplying the second-hand market, electrified corporate vehicles will increase acceptability and accessibility of electric cars for European households. The electrification of this market therefore is not only a ‘low hanging fruit’, it has significant indirect impacts on other markets. As such, it is a major element for the electric vehicles (EVs) market to reach a critical mass.

Additionally, corporate cars are highly visible in our cities. By leading by example and supplying the second-hand market, electrified corporate vehicles will increase acceptability and accessibility of electric cars for European households. The electrification of this market therefore is not only a ‘low hanging fruit’, it has significant indirect impacts on other markets. As such, it is a major element for the electric vehicles (EVs) market to reach a critical mass.

Yet, the electrification potential of corporate vehicles remains largely untapped, due to a lack of clear rules and incentives. Indeed, along with main files such the Eurovignette Directive currently under negotiation, and which would be an important incentive for greening fleets, a whole patchwork of initiatives is included in existing and upcoming legislations. We remind that a successful electrification of corporate fleet shall be linked with a strong roll-out of public and private of charging infrastructures. Annex 1 below outlines our positions on these legislative files and why they will suffice to yield the way to a full decarbonisation of corporate fleets.

With no legislative instrument at hand today, the European policy lacks teeth when it comes to electrification of corporate fleets. We invite policy makers to require more and more fleets such as company cars, taxis, leasing and renting companies and delivery vehicles to electrify, and support companies towards this goal.

To do so, we call for the establishment of a new single regulation dedicated to the electrification of corporate fleets.

Call for a new proposal on the electrification of corporate fleets

A new legislation on the electrification of corporate fleets would set a clear path and objective. This new legislation should include the following provisions:

For a start, such a legislation should equally apply across the European internal market. Therefore, we believe a regulation would be the most suitable legislative instrument to accelerate fleet electrification. The regulation would harmonize the European market by preventing risks of increased gaps between MS during the implementation. This is particularly important for internal market cohesion and regulatory clarity for businesses owning fleet across the EU. A regulation would have the final benefit of having a direct effect.

A realistic yet ambitious mandate should be put on companies to decarbonise their vehicle fleets in accordance with the European Green Deal’s objectives. Fleet electrification is a journey that requires following a roadmap and trials before scaling up in largest companies. Considering the timing of application of the regulation and the ability of companies that recently purchased vehicles or have larger fleets to react a stepwise approach is with interim targets therefore required.

| We recommend setting a gradual approach to progressively but eventually reach the objective of 100% of new vehicle purchase in corporate fleets to be electrified by 2030. |

To avoid imposing a heavy burden on the smallest companies, the regulation should apply to fleets above a certain size. Thresholds should be based on a robust methodology to consider the different segments, industries and MS characteristics while keeping in mind the lower the threshold, the higher the incentives should be for smaller fleets. Next to the electrification of the corporate fleets, companies should consider multimodal packages where a Zero-emission vehicle is combined with other sustainable transport solutions.

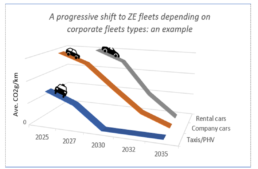

The Regulation’s provisions should differentiate between fleets in their capacity to make the change based on their usual turnover and nature of the transport they perform. Some fleets should face stricter and faster pace to electrification while other could be given more time to electrify. For example, new taxis and private hire vehicles (PHV) committed to drive fully electric vehicles should be issued licences in priority over ICE drivers while fleets in specific industries with technological obstacles (e.g. logging/lumbering industry) may be given derogations.

Along with mandatory targets and compliance mechanisms, incentives for fleet owners will also be needed at European and national levels to accompany the shift. Inspiration for positive incentives should be drawn from lessons learnt from well-designed benefit in kind systems for corporate cars across MS. The Platform for electromobility will soon propose a document outlining such best practices.

[1]https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/transport-emissions-of-greenhouse-gases-7/assessment

[2]https://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2020_10_Dataforce_company_car_report.pdf

[3] EU Commission Expert Group on Clean Bus Deployment; D2 Procurement and Operations.

[4] Flagship 1 – Boosting the uptake of zero-emission vehicles, renewable & low-carbon fuels and related infrastructure

[6] https://www.acea.be/uploads/press_releases_files/ACEA_buses_by_fuel_type_full-year_2020.pdf

[7] In this paper, we include into corporate fleets all “Vehicle owned or leased by a private a company, and used for business purposes.”

[8] https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/cz/Documents/consumer-and-industrial/cz-fleet-management-in-europe.pdf.

[10] DG Climate Action, European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/transport/vehicles/docs/2nd_hand_cars_en.pdf

[11] “Accelerating fleet electrification in Europe”, Eurelectric, 2021 (www.evision.eurelectric.org)

[12] Infographic on assessing the feasibility (https://evision.eurelectric.org/infographics/) – with examples of several fleet use-cases / Eurelectric